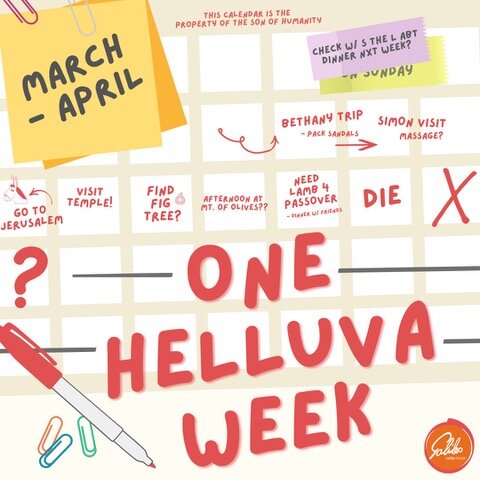

One Helluva Week

Galileo takes the Holiest Week very seriously, from Palm Sunday through double Easter celebrations. How about this year we s-t-r-e-t-c-h out our contemplation of that last week in Jesus’s ministry, the way the gospels do? There’s way more material than we usually have time to dive into in the rush of that singularly hectic week.

For three of these weeks, we’ll have a longer narrative (gospel) reading than usual; we’ll divide that reading at some point that makes sense so that our worship continues to have a first (responsive) reading and a second reading.

Sundays are for palms and protest. The ride into Jerusalem is a satire of militaristic commanders-in-chief returning from battle to receive the accolades of their citizenry. Jesus declares a new empire, a new citizenry for any who will receive him and his way of being – more like a colt than a steed, more like a children’s pageant with makeshift props than a well-orchestrated, red carpet affair. He’s mocking their (our) collusion with domination by violence; he’s challenging our sense of what “good society” looks like.

Midweek is for fig-cursing, table-turning, fight-picking. The way Mark tells it, Jesus does not go to Jerusalem until he’s ready for the fight that’s waiting for him there. He signals in every way that he is up to the challenge, that his ministry is not about compliance or cooperation with the powers that be for his own comfort or elevation. How have his followers in this age gotten this so wrong? When did we become puppets of the U.S. American empire?

Thursday is for dinner, prayer, and the longest night. Before the fracas-to-come, Jesus will take a time-out for (a) a meal with the people he loves most in the world, and (b) somewhat argumentative communion with God’s own self. He seeks comfort, solidarity, release; he receives none of that. What do we learn here about the nature of friendship? And about God’s own positioning, relative to our suffering?

Worst Friday Ever. “The crowds” who have, up to now, been with Jesus, take a turn in this chapter. Taken together, they magnify each other’s worst instincts to violence, disloyalty, and scapegoating. The chapter can be read as a growing consolidation of opposition (crowds, friends, soldiers, VRPs), until even the co-crucified criminals are taunting him – and, in a horrifying turn, until even God abandons Jesus. Could it be that his perception of divine abandonment is a result of the multiple defections of humans from his defense?

Saturday in lockdown: shhh. A question we rarely dare to ask or answer: has God ever disappointed you? It is the right question for Holy Saturday, that desolate day between crucifixion and resurrection. It is the day that we seriously wonder if maybe, maybe, all really is lost. Our journey with God is punctuated with Holy Saturdays – days between the worst and the best, days spent in quiet hiding, dealing with (or avoiding) the deep terror that maybe this time it won’t get better. There is no gospel text for Holy Saturday – surprise, surprise. But there are biblical expressions for it…

Afraid. Mark’s gospel ends so weirdly, with nobody saying anything about that empty tomb because they’re afraid… So we should contemplate what got them from fear to proclamation – how were they eventually prompted to tell? How do we ourselves move from fear to confidence in our announcement of the gospel? (What are we afraid of?)